A Wide Surmise: The Cabinet of Angela Carter

- markdestewart

- Jul 13, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Jul 14, 2025

by Mark Stewart

“One beast and one beast only howls in the woods by night.”

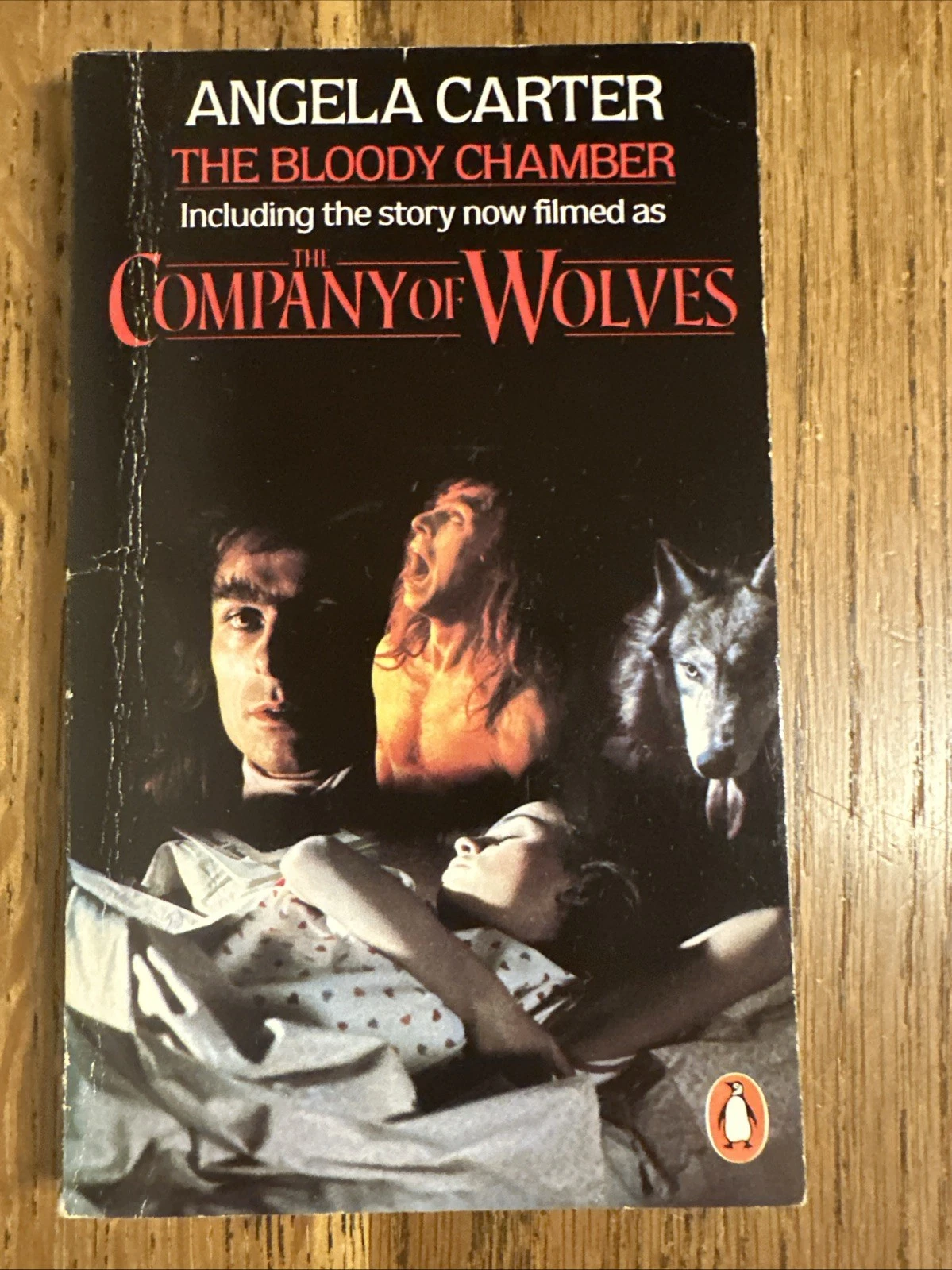

The Bloody Chamber

Angela Carter

By way of preamble: The windblown pamphlet finds its way to the punters feet as he walks down Exhibition Row, with no particular destination in mind. He bends to retrieve the piece of literary driftwood, if such it is, his curiosity piqued. He knows the world to be a random place and he is, one might say, a disciple of the entropic, of the chaos and disorder that is the natural state of the universe. He starts to read the pamphlet, aware that he is already being played, enticed to enter the nearby gallery, to take part in —

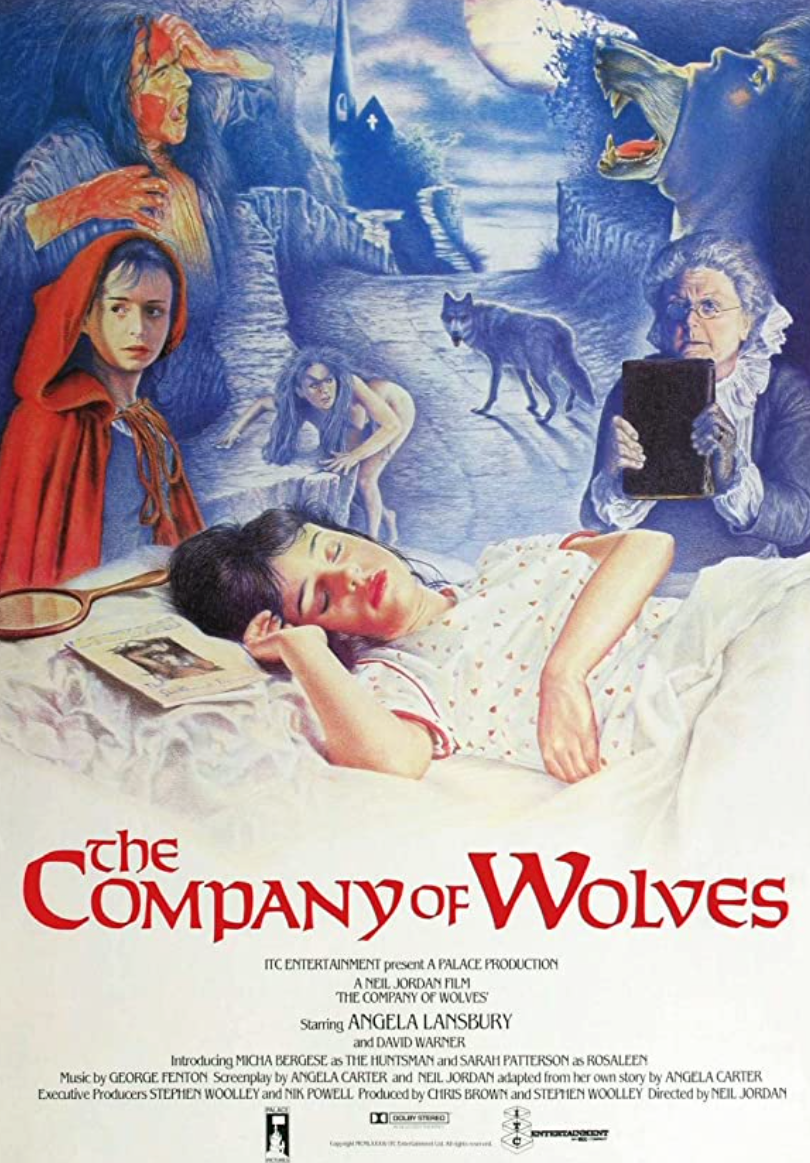

The Entropy Exhibition: Programme Notes: Dedicated to the memory of the British writer Angela Carter, the display depicts a scene from one of her most famous short stories, The Company of Wolves (from her 1979 collection entitled The Bloody Chamber). The display can loosely be regarded as a companion piece to Exhibit Six: Who’s Afraid of the Virgin Wolf? Parental caution is advised for younger visitors to this part of the exhibition, who may find this inversion of the Red Riding Hood fairytale unsettling.

“Everyman”: Ordinary or typical person (Oxford Illustrated Dictionary). Hence I/We/You (The Reader), one of many at the funeral, if such it is, a gathering of familiars deep in the forest, the mourners wary of the dusk and the coming night, all too aware that only one beast makes such a sound, the sound of a soul that can never return to the mountains of the Moon. That longs for the human heart it can never possess, a prisoner of its own solitude.

*

A fearless rider, her skirts blown back by the wind, her hat long gone, galloping across tidal planes, across the ambiguous margins between land and sea, brought the news: dead at fifty-two. The shock a palpable apparition, a messenger we all wanted to slay. Surely that cannot be right? Who, these days, dies so young? What of the mysterious pentangle that was supposed to protect her, beneath which she composed stories the likes of which no one had told before, each as imperishable as a petrified orchid? How had that cloak been breached? And what would become of her offspring? What of Melanie and Finn; would they, did they, ever have children – ginger haired and plump – of their own? Now we would never know.

And the fate of Marianne after the death of her barbarian lover? What became of the Professor’s daughter who chose to live with a man that was both a hero and a villain, as most men are to a greater or lesser degree. Jewel, the impossibly named prince of the cavalcade, doomed the moment he fell in love with Marianne. Another character consigned to literary limbo. Another figure for the cabinet, frozen in place upon the page as he gazes at his headstrong bride, picking at his fingernails with the tip of a much-used blade.

Into the cabinet goes naked Melanie poised forever in mid-cartwheel, as she explores the newly discovered realm of her own body, while Edward bear and a half-read copy of Lorna Doon lie forgotten beneath her bed. Melanie in her mother’s bridal gown trapped in the tree outside her bedroom, unable to cross from adolescence into womanhood. And if there is space for Melanie in the cabinet then there must be room for Finn too. Finn in his fireman’s jacket with his grubby dog-eared business cards: Magic toy repairs: no job too small: contact Finn Jowle. Except now we can’t contact Finn, not in any life he may have had beyond the circumference of Uncle Phillip’s house. Who didn’t cheer when that house, and all the parsimonious misery it contained, burnt down, freeing its former occupants from the puppet maker’s tyranny?

The Countess may be gone but we can still share the company of the transmorphic wolves that were so often her muse. Now you see them, now you don’t, slipping like grey wraiths between the trees, shape shifting into human form and back again, crossing the uncertain frontiers between sleeping and waking, between reality and dream. “What sweet music they make,” says the Count, as he licks blood from the cut-throat razor with which he has dispatched the latest visitor to his impossibly heraldic castle, one whose crenulations adorn the summit of a Carpathian mountain. And what sweet words they inspired. Prose so close to poetry that it was hard to separate the two. And therein lay the problem: once you discovered a cabinet of such outlandish possibilities, all so magically real, nothing else came close. To this day, magical realism begins and ends with Angela Carter.

Did the young Angela spend her nights at the circus and her days in a magic toyshop, a wise child raised by a new Eve? If so, it was time well spent. The essence of her literary style was that nothing is quite what it seems. It’s what we learn in the very first stories we ever encounter, in those that are read to us as children. You say she exaggerates her narrative style? Very well, she exaggerates. But never to excess, never beyond the limits of the plausible. And is that exaggeration not closer to the truth than plain reality ever can be? What writer, worthy of that appellation, isn’t guilty of such misdemeanors? Surely, in terms of sheer reading pleasure, the guiltier the better for who wants to hear a story constrained by boundaries, by the self-imposed frontiers of an impoverished imagination? Kitchen sink dramas produce tales as dull as dishwater and narrative colour was what Carter’s stories had in abundance, her writing glowing with lyrical intensity. Each fable was full to the Plimsoll line with images that were strange, vivid and erotic, so much so that it was hard at times to pull your eyes away from the page.

Into the cabinet go the prayer books, the lush leather-bound volumes containing images of the Sultan’s harem, stumbled upon by the young bride of the Marquis. A discovery which seals her fate as fodder for the Iron Maiden, condemned to death by a thousand penetrations, none of them kind, none of them tender. Or so it seemed. Carter’s heroines never succumbed to the banalities of men, to their all too predictable fetishes and infernal desires. Not without a fight, and not without coming out on the winning side.

That’s why the news came as such a shock. Someone who championed determined and resourceful female characters, and who had put up such a fight herself, lost so early on in the war against cliché. The funeral must, should have been, a gothic affair, conducted in a Wagnerian setting. Not the tacky melodrama of adolescent self-indulgence but the high romance of Bronte’s most famous lovers. For the moors and the woods were never far away in the landscape of Carter’s imagination. Beware the moors after dark! Or to put it another way, if you go down to the woods today, you’d better go armed to the teeth. The perilous ground that always began just a few steps from the front door to granny’s cottage. A danger that Tolkien was also keenly aware of: "It's a dangerous business, Frodo, going out of your door. You step into the road, and if you don't keep your feet, there is no knowing where you might be swept off to."

Where did the road end for the queen of the short story? A polished obsidian locomotive, as dark as a raven’s wing, its name Nevermore displayed on raised letters on the side of the engine, carrying her body through the countryside. Across those very same moors, until it could go no further, halted by an impassable bridge. Then a carriage drawn by black horses adorned with white plumage, urged on by a spectral coachman, to the final resting place. The mourners gathered beneath torches, one ear on the surrounding countryside for the sound of her trusted familiars. The lamentation of the lycanthropes not for the unreachable forests of the Moon, not this time anyway, but for the passing of Red Riding Hood herself, now grown to mortal adulthood. Amongst the mourners, Lizzie Borden, her innocent axe long laid to rest. And at the outer fringes of the gathering, at the edge of the wood, the Erl King himself, wondering how best to beguile at least one of the mourners, so that he might return home with his supper.

Into the grave with the first handful of earth would surely go the fatal rose that Beauty’s father plucked from the garden of the Beast, condemning his daughter to be sold to meet debts no honest man could pay.

Which of the many maidens was Carter herself? All? None? A fragment of each, each vignette revealed in passing like images glimpsed in a hall of mirrors. If there can only be one, then perhaps The Lady of the House of Love is the most plausible fit. The achingly mournful beauty who inhabits a desiccated chateau, endlessly searching her tarot cards for a way to escape the dreadful fate bestowed upon her by her baleful ancestors. This is the body inside the catafalque that is also the home of the fatal rose.

That same rose grows now on her grave in solitary splendour more fitting than any marble headstone. Like her stories it will never die, nurtured as it is by a deep well that many writers search for (sometimes over the course of a lifetime) but which few are fortunate enough to find. The Lady of the House of Love will always sit in her spectacularly dilapidated boudoir, waiting for the next traveller to enter the crumbling courtyard and drink from the fountain. To find his way to the heart of her chateaux guided by a welcoming old crone, where he might examine a cabinet of fabulous possibilities.

Gazing at each exhibit, as Melanie and Finn had once done, across a wide surmise.

*

The Tiger’s Bride

My father lost me to the Beast at cards…so now I must save myself, and my skin is all I have. Longing to be free, I unzip my spine, as if shedding a dusty trousseau, a gown unloved and seldom worn. Arms reversed over my head, plucking each vertebra as one might a frozen rose. Like wooden bricks they clatter to the floor. My fugitive self free to roam.

Neither hero nor villain, my time misspent. My nights at the circus, my days a shadow dance. Tutored by wise children, my home a magic toyshop or a bloody chamber.

Thus un-sleeved I enter the cat’s pelt, complete at last. Inserting one limb at a time, until – hand in glove – I can feel myself flex, sealed within my new pelt. My padded pus-purr feet, my febrile whiskers sampling the air, each filament as sensitive as a sea anemone.

My backbone a swaying, sauntering tail, like a second shadow off about the town. A chancer on the prowl looking for mischief. My fingers as sharp as any blade, each a retracted stiletto, a jack-knife waiting to be sprung. Examining my claws with their hidden weaponry, so stealthy, so serene, I contemplate an infinite array of possibilities, gazing across a wide surmise.

I clean my newly furred skin with a rasping tongue, feeling the contoured flesh for the first time. My careful ablutions arrested upon the moment by nerves stretched tighter than the sensorium of a shark.

Yellow slits for eyes, each narrow iris a doorway into ancient jungle. Focused now upon my prey.

Upon you.

Here, kitty...

(In memory of Angela Carter 1940-1992)

Comments